Forty seven years of my life was spent as an airline pilot flying jet aircraft. During that time I experienced two calamitous engine failures, one of which was accompanied by a raging fire. On a third occasion I had two of the four engines on a Boeing 747 flame out while conducting a high altitude test flight.

The jet-turbine aircraft engine is nevertheless an incredibly dependable power plant. Manufacturers of these engines are obliged to achieve a reliability factor of less than twenty failures or shutdowns per one million flying hours for each engine model that they produce.

However, the actual figure being achieved in this day and age is close to two engine shutdowns per million hours. This statistic is both astonishing and comforting.

“Engine failures do occur”

Unfortunately, from time to time, engine failures do occur. These usually happen in one of two different ways.

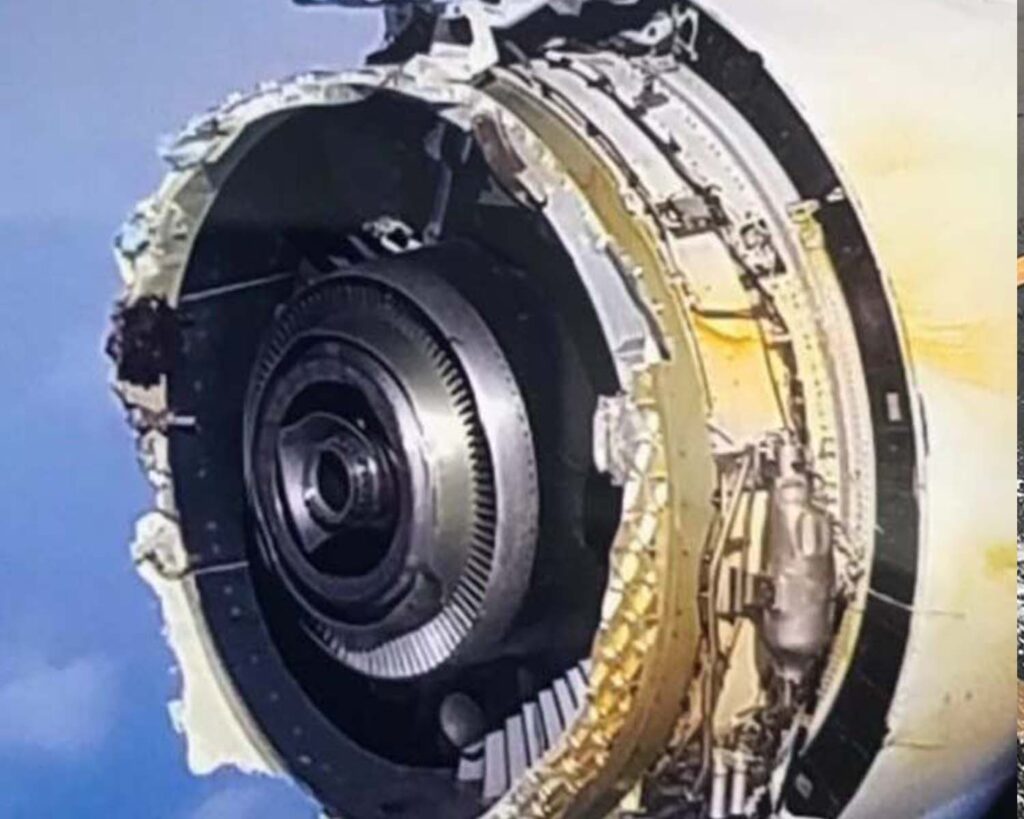

There could either be a straight “flameout”, or there could be a major failure of engine components and accessories that lead to the occurrence of severe damage, a fire, or even a separation of the engine from the airframe.

In certain cases an engine that is showing indications of a malfunction may need to be shut down as a precautionary measure since further operation thereof would be likely to result in it incurring additional damage.

Instruments that provide information

There are a number of instruments that provide information to the pilots as to the thrust output and condition of the engines.

In general, for each installation there is an N1 indicator which shows the r.p.m of the large fan at the front of the engine and which provides the air for the low pressure compressor.

An Exhaust Gas Temperature gauge indicates the temperature of the heated air in the vicinity of the turbine.

An N2 indicator gives the r.p.m. of the high pressure compressor in the middle of the engine that provides high pressure air for the turbine. This compressor also drives various engine accessories.

Other important engine gauges and warning lights display the normal operating ranges, caution ranges and operating limits for various engine sub-parts and functions. These include the fuel flow, the state the engine fuel and oil filters, the level of vibration of the engine and the oil temperature, pressure and quantity.

Engine malfunctions

An engine malfunction or failure could occur at any stage of a flight. In the first three or four seconds following such an event, maintaining control of the aircraft and ensuring a safe flight path is of paramount importance.

The reason for the failure might not be obvious, so, based on an interpretation of information provided by the instruments and associated warning signals plus any other available resources, a careful assessment of the problem must be made.

A general rule of thumb is that if the N2 compressor is still rotating without any vibration and there is no indication of a fire or an excessive EGT, severe damage to the engine would be unlikely.

Reading of an “Engine Failure or Shutdown” checklist would be done in order to contain the problem. This checklist would only be referred to when the flight conditions allowed and not necessarily as a matter of urgency.

If, on the other hand, as another very quick rule of thumb, the N2 compressor was not rotating, as evidenced by a “Zero” N2 reading, severe damage would more than likely have occurred.

Other pointers could be excessive vibration, oil system “red line” indications and fire warnings. If this sort of situation existed, the “Engine Fire or Engine Severe Damage or Separation” procedures would need to be actioned and the associated checklist to be read just as soon as the crew could possibly do so.

Following checklists for abnormalities

When following checklists for abnormalities, the presence of the word “CONFIRM“ is often displayed. It is written in places where a confirmation from both pilots must be obtained before a particular action is accomplished.

The reason for this is because many actions are irreversible. If the wrong switch or lever is selected, an entire aircraft system could be disabled, possibly leading to a disaster of mammoth proportions.

As a particular example, most engine fire and severe damage checklists call for three “confirmations” during their execution.

The first is when the thrust lever of the affected engine is closed so that a positive identification of the engine to be shut down is made. Next is for the engine start lever that will be moved to “cut-off”, thus shutting off fuel to the engine. The third is for the fire handle that will be pulled and which will disable the engine’s air, fuel, hydraulic and electrical systems, whilst at the same time arming the appropriate fire protection system.

For an engine shutdown without severe damage, the associated checklist is done as a “read and do” checklist and only when “flight conditions allow”.

If an engine fails and the indications are that severe damage has occurred, with or without an accompanying overheat or fire, the associated procedures require immediate action. The actions are done by recall before reference to the checklist is made. When the required actions have been accomplished, reading of the checklist, treated as an “action” checklist, takes place.

The handling engine abnormalities must always include a proper identification and assessment of the problem, an appreciation of the level of urgency that exists and then the application of the appropriate procedures.

Disclaimer: The information provided in these tutorials is suggestive of reasonable operating philosophies. It should not preclude sound airmanship and proper decision making and should apply to the appropriate sphere of operation being addressed.